《海海臺東.南島誌》2025年雙語選輯 :::

《南島,以藝術之名》作者潘小雪專訪/Interview with Yuki Pan, Author of "Nan-taw: In the Name of Art"

文Writer|南美瑜 Mei Yu Nan 圖Photographer|林庭宇 Ting-Yu Lin、Makotaay Eco Art Village 翻譯Translator|加州翻譯社California Translations

原文出處|《海海臺東.南島誌》Vol. 4,2025年9月號

潘小雪Yuki Pan

前言/Introduction

《南島,以藝術之名Nan-taw: In the Name of Art》作者潘小雪,長年棲居於花蓮,她的身心靈故鄉。這段書寫交織著作者跨30餘年的時光、豐富的跨領域對話,除了如實呈現已經發生的、以及正在發生的南島藝術現象之外,她希望藉由書寫出臺灣原住民藝術創作的本質與藝術主流大不相同之處,用以沉思藝術......。 Author of "Nan-taw: In the Name of Art" Yuki Pan has lived for years in Hualien, the home of her body, mind, and spirit. The book spans over 30 years of her life and the rich cross-disciplinary dialogue that took place over that period. Apart from faithfully presenting Austronesian artistic phenomena that have already occurred and are currently unfolding, she wants her writing to relate the major differences between the nature of Taiwanese Indigenous people’s art and mainstream art as a means of pondering art….

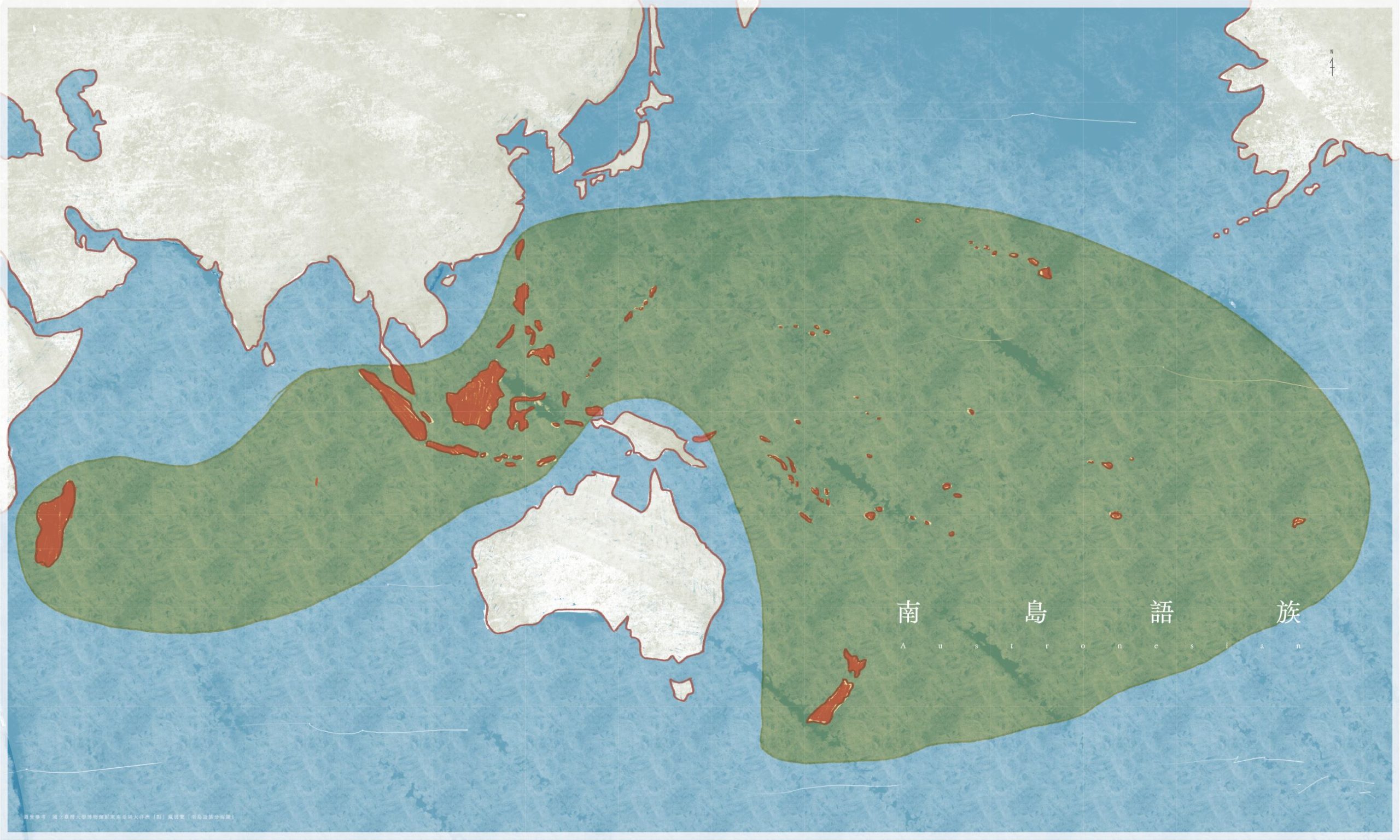

南島美感拓樸/A topology of Austronesian aesthetic

1990年代的臺灣,為了突破政治困境,引發各領域的積極行動;學術界針對太平洋、大洋洲、南島語族領域進行深入探討。出身美術學院、畢生研究美學與哲學的她,了解到關於起源理論的探討,例如以語言學、人類學探討南島起源時,如果過於強調單一原鄉、線性史觀,必然會面臨二律背反、悖論不完的惡性循環。而藝術主流已開始走入過度形式主義的僵局,所以當「南島藝術」成為政策、策展題目或論述時,也會出現同樣的定義問題。 In the 1990s, to find relief from Taiwan’s political predicament and trigger action by people in various sectors, academia began conducting in-depth research on the Pacific Ocean, Oceania, and the realm of Austronesian-speaking peoples. Having graduated from a school of fine arts and devoted her life to the study of aesthetics and philosophy, Pan gained insight into the exploration of origin theories. For instance, while probing the origins of the Austronesian-speaking peoples through the fields of linguistics and anthropology, she found that if too much emphasis is placed on a single homeland or if a linear view of history is taken, one will inevitably be faced with a vicious cycle of contradictions and paradoxes. Mainstream art embarked on a deadlock of excessive formalism, so when Austronesian art became a government policy, curatorial theme, and topic of discourse, the same problem of definition emerged.

《南島,以藝術之名》,潘小雪著,臺東縣政府、臺東美術館出版,允晨文化發行。

但南島一詞並非藝術生態所形成的觀念,潘小雪的書寫也不在於提出新的主義,而是用貌似「講東講西」的姿態詮釋這個正在發生中的、貫穿時空的、靈與人的「流形」空間,想像一個以藝術為名的南島美感拓樸(Topology)。誠如人類學者林浩立所言,「撬開文化觀念的槓桿是關於書寫與拼貼的延伸概念,前者被認為互動性、開放性與過程性;而後者則是要為異質性提供空間,不僅是為美學並置,更是為歷史並置和政治並置提供空間。」(注) But the word “Austronesian” did not come from the art ecosystem, and Pan’s writing is not about proposing another -ism; rather, she has interpreted this unfolding, across-time-and-space, spiritual-and-human “manifold” space in a “rambling” manner so as to come up with a topology of Austronesian aesthetic in the name of art. Anthropologist Lin Hao-li was spot-on: “The lever for prying open cultural concepts lies in the extended notions of writing and collage: the former is understood as interactive, open, and process-oriented; the latter seeks to provide space for heterogeneity for not merely aesthetic juxtaposition but also historical and political juxtaposition.”* 注|報導者「Boom・磅」講座:林浩立「南島—太平洋是21世紀最繽紛迷人的『成為原住民』路徑」),陳怡靜記錄,2024年12月。 * From The Reporter. Chen Yi-ching. December 2024. Boom: Lin Hao-li: “The Austronesian–Pacific Region Is the Most Vibrant and Fascinating ‘Path to Becoming Indigenous’ in the 21st Century.” (Article published in Mandarin only.)

重回部落找回原初/Returning to Indigenous communities to rediscover primality

事實上,許多臺灣原住民藝術家並未用南島為概念去創作,「他們在傳統與現代之間復返與拓展,為臺灣創作新的藝術知識(或返回藝術的本源找到真實),他們的態度是自由面對的。」不少學院出身的創作者卻常陷入技術訓練的養成所形成的侷限,「要丟掉往往得花一輩子的時間。」潘小雪說。 In fact, many Taiwanese Indigenous artists make art unrelated to Austronesian issues. Pan says, “They oscillate between the traditional and the modern, reclaiming and extending it, creating new artistic knowledge (or returning to the origins of art to find truth) in Taiwan. They do so freely.” Many artists from art schools often fall victim to limits that form as a result of technical training. “It often takes a lifetime to break free.” 藝術家該如何得到解脫與救贖?幸而長年在教育現場的她,往往是從不被主流價值認同的、被視為「問題學生」的年輕人身上,看見了不受框架限制、天馬行空的創造力與想像力,繼而得到啟發。而更重要的是進入部落學習,這是她成長中缺席的一塊,但在銅門國小前校長陳明珠等友人的引領下,參加多次部落的祭儀活動,尤其是花蓮Makotaay港口部落豐年祭,熟稔原住民文化的陳明珠以現代語言為她剖析深度的內涵;也常遇見從都市返鄉,投入部落事物、復振文化如拉黑子等原住民創作者們,讓她目睹「藝術正在發生的那個當下、那個現場」。 So how do artists liberate themselves? Fortunately, she has spent years in the education realm, and it is usually from young people who are not recognized by mainstream values and who are labeled “problem students” that she sees creativity and imagination unbounded by conventional frameworks and is thus inspired. More important is learning in Indigenous communities, which is something she missed out on while growing up. But with the guidance of Chen Ming-chu (the former principal of Tongmen Elementary School) and other friends, she attended several ceremonial events in local Indigenous communities. At the harvest festival in the Makotaay community, Chen, who is well-versed in Indigenous culture, explained to her in readily understood language the profound things that were happening. Also, such artists as Rahic Talif, who return to and invest themselves in their home communities and work to revitalize local culture after having lived away in cities, have shown her “art as it is happening and where it is happening.”

當代藝術半路遇到原住民/Contemporary art meets Indigenous art

2002年初春,臺東有一群藝術家在金樽沙灘紮營長達三個月,他們分別來自花東各部落、也有白人與白浪(漢人),沒水沒電、就地取材造屋、創作、辦展覽,自稱「意識部落」。至今,這股回歸原初的創作能量依然深深影響著東海岸的藝術發展。而潘小雪則從2003年開始,策劃主辦洄瀾國際藝術家創作營,其後十年之間持續和世界各地藝術村合作,在花蓮各個重要歷史空間以及部落舉辦創作營,總共邀集32個國家(遠及聖彼得堡、布宜諾斯艾利斯、開羅、亞美尼亞、南非等)72位藝術家與73位臺灣藝術家參與,「用極少的經費在現實中建構一個藝術烏托邦。」 In early spring 2002, a group of artists from Indigenous communities on the east coast as well as some of Han-Chinese descent and from abroad camped at the Jinzun beach in Taitung for three months. Without running water or electricity, they built structures, made art, and put on an exhibition, all using local materials. They called the camp the “Open Circle Tribe.” That surge of creative energy making a return to primality is still influencing art along the east coast. In 2003, Pan started curating the Hweilan International Artists Workshop and, over the following decade, worked with art villages around the world while holding art workshops at major historical spots and Indigenous communities in Hualien. During that time, she brought together 72 artists from 32 nations (including places as far away as St. Petersburg, Buenos Aires, Cairo, Armenia, and South Africa) and 73 Taiwanese artists, “building an artistic utopia with minimal funding.” 在駐村期間,國外藝術家們尤其喜歡跟原住民在一起聊天、工作,白日裡,在鏈鋸聲、收音機音樂聲、笑聲不斷的氛圍中開始一天的工作。原住民創作者流暢地操作電鋸、綁鐵線、釘釘槍、鎖螺絲等勞動本領,與熱心地幫助分享的個性,讓國外藝術家既讚嘆又感動。夜裏,在工寮、沙灘各式場域的創作論壇中,原民藝術家分享著如何為捍衛文化與土地而創作,生命處境與生活經驗內化而成的身體感反映在作品上的能量。 During the workshops, the overseas artists were particularly fond of chatting and working with the Indigenous artists. During the daytime, the sounds of chainsaws, radios, and continual laughter filled the atmosphere. Indigenous artists, highly adept in their use of tools, were more than willing to help their foreign counterparts, leaving the latter both impressed and moved. At night, during forums held in work sheds and at the beach, Indigenous artists shared about how they create art to safeguard their culture and land, and the feelings—shaped by their life circumstances and experiences—that manifest as energy in their work. 曾有一位巴勒斯坦藝術家在聽完分享後,淚流滿面地問,「為什麼有人可以這麼愛自己的族群、靈魂和土地?」這位藝術家從小在異地受教育、定居海外,他從不知道要跟哪一塊土地結合。潘小雪看得出原民藝術帶給其他藝術家的衝擊,「他們知道這裡面(部落)有好東西!」「而他們(原住民)一直在進行的是藝術『在發生時』的那個狀況,他們體現的是藝術創作的原初性。」是這麼充滿原始的生命力與強度!當主流社會的當代藝術想要回溯藝術的原初性時,「他們在半路碰到原住民藝術,而帶來了啟發。」 After hearing an Indigenous artist share, a Palestinian asked in tears, “How can someone love their people, soul, and land so much?” The Palestinian had been raised and educated outside of Palestine and did not know which land he should connect with. Pan saw the impact Indigenous art produces on other artists: “They know there’s good stuff in Indigenous communities! And the art Indigenous people create is that which is in the very moment of its occurrence. They manifest the primality of art.” Indigenous art is imbued with so much primal energy and power! As mainstream contemporary artists were looking to make a return to primality, “they happened upon Indigenous art, which is generating new inspiration.”

當代藝術是全人類性的/Contemporary art is for all of humanity

「當代藝術(contemporary art)是在談正在發生的事,是很即時性的,暫時是用這樣的創作議題來解釋、批判,許多議題更是屬於全人類性的。」「所以人人都可能作為當代藝術家,這也是即使沒有受過藝術教育的原住民創作者自然產生的原因。」潘小雪說。 “Contemporary art is about what is happening now. It is immediate. It interprets and critiques, and many of the issues it deals with are of universal significance. So anyone can be a contemporary artist. That’s why Indigenous people without any art education background have naturally become artists,” Pan says. 前高雄市立美術館館長李俊賢(1957-2019)於2006年率先提出「南島藝術」這個觀念與詞彙,是最早提出「重啟臺灣原住民當代藝術與南島語族當代藝術之連結」的藝術機構首長與藝術家。由他主導與串連全球的大型國際展覽中,在交流、立論非常豐富而有深度,如2007年舉辦的「超越時光.跨越大洋— 南島當代藝術」大展 ( Across Ocean and Time—Art in the Comtemporary Pacific ),李俊賢與協同策展人艾曼紐・卡薩耶胡(Emmanuel Kasarhérou)的論述奠定南島藝術的思想內容主要有三方面:一、大洋洲、太平洋、南島語族諸島是海上人類文明的基地。二、關係連結新力量。三、當代藝術是全人類互動的方法。 Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts director Li Chun-hsien (1957-2019) coined the term “Austronesian art” in 2006 and was the first head of an art organization and the first artist to propose “reinitiating the connection between contemporary Indigenous Taiwanese art and contemporary Austronesian art.” During large international exhibitions guided by him that connected different parts of the world, the exchanges and discourse that took place were enriching and profound. For instance, during the 2007 exhibition Across Ocean and Time—Art in the Contemporary Pacific, Li and co-curator Emmanuel Kasarhérou established that the idea of Austronesian art has three main aspects: 1) Oceania, the Pacific, and the islands inhabited by Austronesian-speaking peoples were a collective cradle of maritime human civilization, 2) new power in building connections, and 3) contemporary art as a means of interaction for all of humanity. 2024年,威尼斯雙年展金獅獎最佳國家館由澳洲館獲得,主題展「最佳藝術家獎」則由紐西蘭的Mataaho Collective獲得,兩者皆是原住民藝術家及其創作。潘小雪認為,這正說明了過去以西方為主流的藝術世界「有待靠原住民藝術來『解救』。」 In 2024, the Venice Biennale Golden Lion for Best National Participation went to Australia, and that for Best Participant in the International Exhibition went to New Zealand’s Mataaho Collective, both of which were groups of Indigenous artists. Pan believes that the art world, which has long been dominated by the West, “is to be ‘saved’ by Indigenous art.”

2023年Makotaay生態藝術村開幕石梯漁港Mihoyo現場,潘小雪(右)說自己已是ina(Pangcah語為母親、阿姨)的身分了。

當隱喻正在發生/When a metaphor is unfolding

此書的英文書名南島二字並未採取語言學所使用的Austronesia,而是以Nan-taw稱之,潘小雪企圖用藝術來探討南島其他意義的可能性,尤其是她從人類學者童元昭自艾培立・浩鷗法(Epeli Hau'ofa 1939-2009)的「我們是海洋」觀點,以其延伸思想「南島是一個隱喻(metaphor)」這個創造性的角度所帶來的啟發。既然是隱喻,便能擺脫掉理論讓人悖論不完的死胡同;當南島成為一個隱喻,也說明了它在審美上的無限可能性。 In the English name of this book, the transliteration “Nan-taw” was chosen in place of the common linguistic term “Austronesia.” Pan is attempting to find other possibilities for the meaning of “Austronesia,” an endeavor especially inspired by anthropologist Tung Yuan-chao, whom Pan once heard give a presentation that mentioned Epeli Hau'ofa’s (1939-2009) concept that “we are the ocean” and introduced a creative extension of that: the idea that “Austronesia is a metaphor,” and since it is a metaphor, it frees us from theoretical dead ends that trap people in endless paradoxes. As a metaphor, it has unlimited possibilities in the realm of aesthetics.

原住民有一個字叫自來手,概念與pulima(巧手之人)類似,「其實就是我們上輩子做過的承諾,因為在生命最終的時刻,想要做卻無法進行的那件事,所以承諾下輩子一定要去做。」「所以我們的手是被帶著走的。」她右手拿畫筆、左手寫評論;曾任美術館館長、藝術學院院長、多次成為公民倡議與運動的前鋒;在籃球場上,她是擅長逆轉勝的中鋒,在創作與書寫中她也擁有那雙靈性的手。 The term “makisa ljanga” is from a Taiwanese Indigenous language and refers to a concept similar to that of another Indigenous concept: pulima (“one with a skilled hand”). Pan explains, “It’s a commitment made by generations past. At the end of one’s life, when there’s something they want to do but can’t, they commit to doing it in the next life. So our hands are brought with us into the next life.” With a paint brush in her right hand and a pen for writing critiques in her left, she has worked as an art museum director and dean of an art school and has been on the front lines of numerous public initiatives and movements. On the basketball court, she is a center who excels at turning the game around. And in art and writing, her hands are spirit-filled. 「從小到大,有規則的比賽,我一定會贏。」像人生中一場場的籃球賽、考試、寫升等論文的無往不利。但當直球對決於政治與現實社會的公民運動中時,她卻因看不到「規則」的存在偶而敗陣。「我其實想要透過實際參與來做自我客觀化的省思:『你到底了解這個世界、涉入現實有多深?』只是因為觀念、閱讀、媒體,就成爲參與(公民運動)的原因嗎?我想了解為什麼會這樣?」 “I’ve always won at games with rules ever since I was little.” She has enjoyed much success in so many of her undertakings: basketball, tests, and papers for promotions. But when it comes to direct confrontation in social movements within politics and real-world society, where the rules are vague, she sometimes loses. “I want to be involved in person as a way to reflect on myself objectively in asking, ‘Do I truly grasp the world? How deeply am I engaged with reality?’ Do I get involved in social movements just because of viewpoints, things I’ve read, or the media? I want to know what is going on in that aspect.” 老人家說,要有智慧回眸人生,專注在那個思想裡面,你就是「被揀選的」、帶著自來手的人。如果自來手是一個隱喻,它說明了藝術創作者一生的創作自覺。而她總是全神貫注投入於藝術和社會的熱情與勇氣,像是在回應那份亙古的承諾。文如其人,她將此書「獻給在這片土地上努力創作的藝術家」。 Those of the older generation say that you need to look back on life and focus on the related wisdom. If you do, you become one of the “chosen” and are gifted with makisa ljanga. As a metaphor, makisa ljanga tells of the creative consciousness of an artist. Pan, brimming with passion and courage, is fully focused on art and society, as if responding to that ancient commitment. One’s writing is a reflection of oneself. She dedicates this book “to the artists who strive to create in this land.”

潘小雪/Yuki Pan

藝術創作、藝術教育、美學研究、臺灣原住民藝術研究。曾任國立東華大學藝術學院院長、台北當代藝術館館長,參與或開創臺灣解嚴後的各項文化政策與藝術運動。早年曾在英國、德國駐村展出、亞美尼雅雙年展、台灣美術雙年展以及七個個展等。曾於比利時新魯汶大學哲學院研究梅洛龐帝美學,啟發個人在原住民藝術的美學研究,由此提供疲敝的人心予野性的思維,恢復生命力。 Artist, art educator, and researcher of aesthetics and Taiwanese Indigenous art. Dean of National Dong Hwa University College of the Arts, Director of MoCA Taipei, participant in or initiator of various cultural policy and artistic movements in Taiwan after the lifting of martial law. Artist residencies and exhibitions in the UK and Germany, International Biennale of Contemporary Art Gyumri Armenia Armenia, the Taiwan Biennial, and seven solo exhibitions. Studied Merleau-Ponty’s aesthetics at the Université Catholique de Louvain in Belgium, which inspired her to conduct research on Indigenous art aesthetics, which in turn restored her vitality by providing her weary heart with a wild, untamed mode of thinking. 原文出處|《海海臺東.南島誌》Vol. 4,2025年9月號